Once I’ve had some time away from my first draft, it’s time to start in on revisions. Naturally, the first stage in revisions is . . . the second draft!

The second draft is the most complicated stage of my writing process, and half the time I feel like I have to re-learn this part with each new book, but I’ll do my best to break it down into something that seems halfway logical…

Note: This is the stage where I start using Scrivener, an organizational software program for writers. I’m a big fan of Scrivener, but it’s certainly not necessary. I’ll include notes following each step for how I used to do this before I had Scrivener.

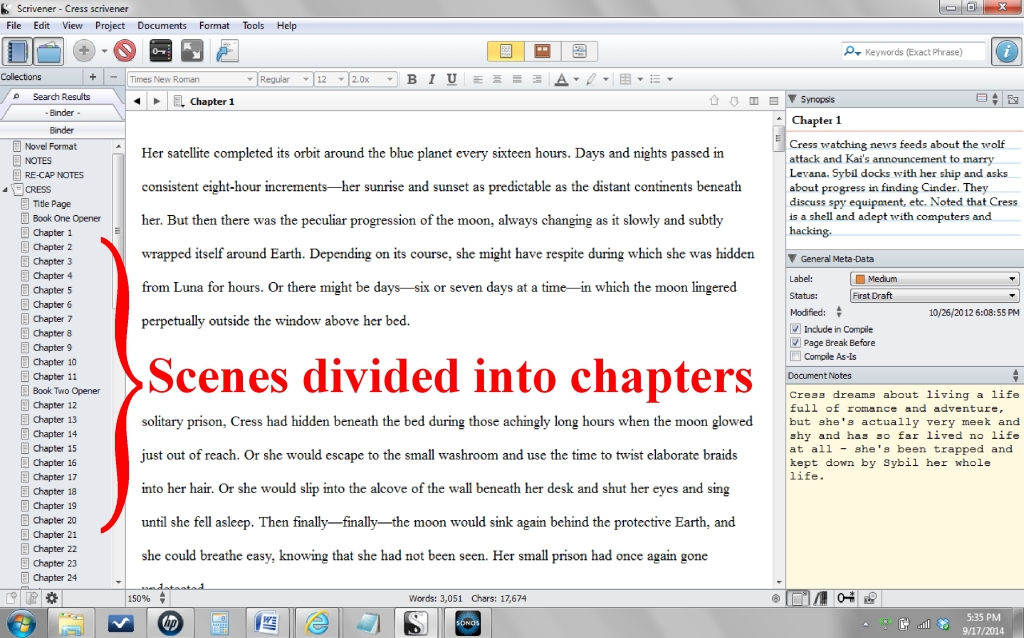

1. Transfer the manuscript into Scrivener.

I started using Scrivener with Cress, and I love it. It really plays to my neurotic sense of organization (more on that later). But I still prefer to write my first drafts in Word, because it’s easier for me to keep track of word counts and my daily word goals.

So for me, the first step of writing the second draft of a book is to transfer the text of the first draft into Scrivener. I separate each scene into a different Scrivener chapter file.

Not using Scrivener? No problem. Skip this step.

2. Read through the first draft.

Reading through the first draft is often a humbling experience. No matter how inspired I was, no matter how thorough my outline, no matter how excited for the story—the first draft is inevitably a disaster. So it goes.

But before we can make anything better, we have to figure out what’s wrong with it, which is why this initial read-through is very important.

I am not making changes when I read this draft. I might fix a typo here or there, but anything more complicated than that gets marked as something to fix later. I try to read the first draft as quickly as possible (within a day or two), so I can get a feel for the big picture.

While I’m reading, I’m simultaneously doing three things:

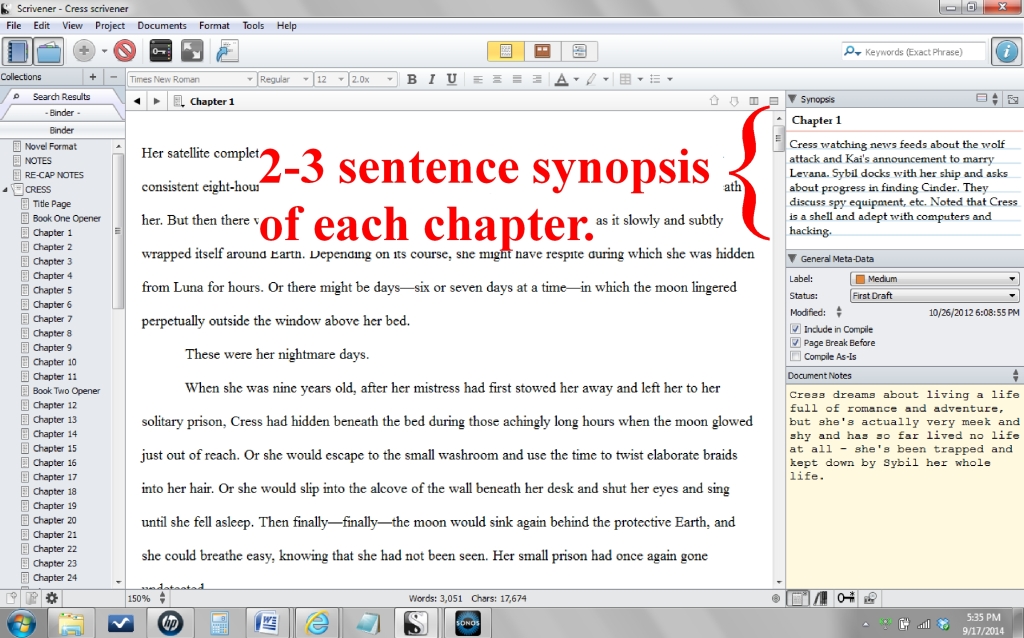

1. I’m updating the synopses (aka notecards summaries) for each chapter in the Scrivener file. This way, when I’m done, I’ll be able to look at the 2-3 sentence summary for each chapter and know what happens in it.

Not using Scrivener? You can do the same thing by making a list in a separate Word file, i.e.:

Chapter 1: Scarlet is delivering food to the tavern. We learn that her grandmother is missing.

Chapter 2: Scarlet meets Wolf in the tavern. She sees Cinder on the netscreens and stands up for her. Brawl breaks out.

Chapter 3: Blah blah blah…

I also call this making my “scene list.”

2. I’m updating my list of BIG changes I want to make (I almost always have a list started from back when I was writing the first draft and already thinking up things that needed fixing). I’m looking for things like plot holes, flimsy characterization, twists that seem contrived, villains that are too boring or too easily defeated, romances that don’t sizzle, and the like.

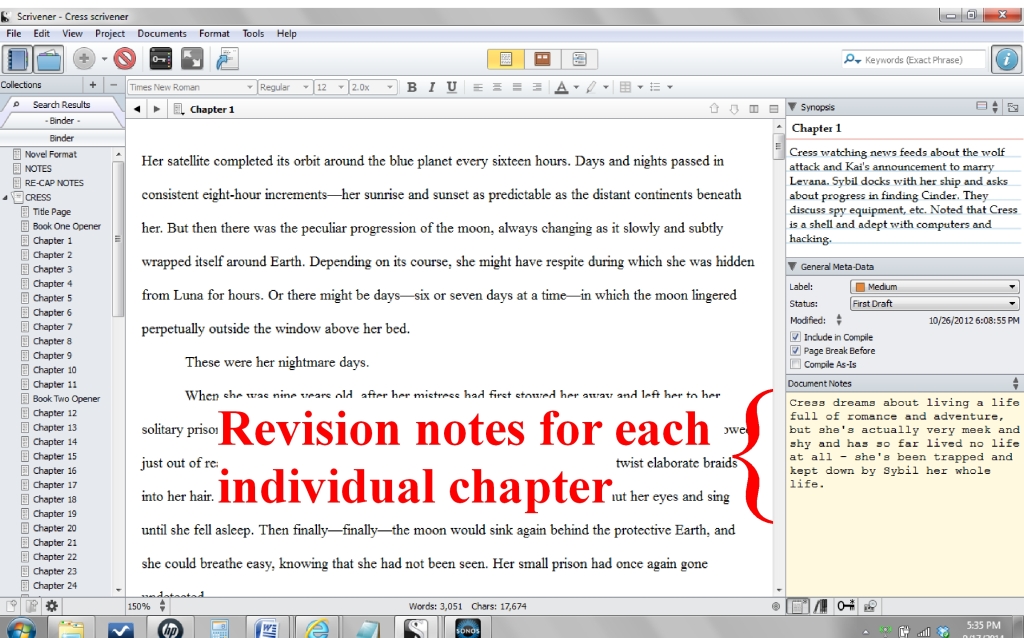

3. I’m noting smaller changes on a chapter-by-chapter basis. I note these changes in the “Document Notes” portion of Scrivener, so that they’re kept separate for each chapter. These will be things like: Insert Iko into this chapter. Or, Give Cinder something to do during this conversation—maybe have her fixing something? Or, Give Thorne a knife here (he needs it later).

3. Plan the Revisions, Starting with the Big Stuff

Once I’ve finished my read-through, I’m starting to have a sense of what’s working in the book and what’s really, really not working. I review those BIG issues I want to fix and start brainstorming solutions.

For example, in the first draft of Scarlet, Wolf had amnesia—he couldn’t remember anything of his life prior to arriving in this small town in France. But in reading that draft, I was unhappy with how passive of a character this made him. I wanted him to be filled with internal conflict that stemmed from conflicting loyalties to Scarlet and to his Pack (which wasn’t possible when he had no idea who or what a Pack was).

So I decided to do away with the amnesia entirely, which changed the basis of a lot of scenes throughout the book. Chapters and chapters had been dedicated to Scarlet and Wolf trying to find out more about his past—hunting down police records and the like—and those chapters now either had to be deleted or altered to fit with Wolf’s new reality. To change something that had been so integral to the plot before is never an easy task, but I knew as soon as I made the decision that the story would be stronger for it.

I go through my entire list of BIG changes this way—figuring out why something isn’t working and trying to come up with something I can do to make it better or stronger. Some solutions come easily, some will plague me for weeks or months. Many things that are bothering me at this stage won’t have feel completely fixed until the third or fourth drafts of the book, but I do my best to start working toward solutions now.

Once I’ve landed on a solution that I think is going to work, I start moving chapter-by-chapter through the book and notating what would need to change in each chapter to exact that change.

In the case of Wolf no longer having amnesia, I went through each chapter and, if it was a chapter in which Wolf’s amnesia was mentioned or impacted the plot, I made a note like: Remove discussion of his amnesia. Or, This chapter no longer relevant—delete. Or, Change conversation and dynamic—Wolf comes to the farm because he has info on Scarlet’s grandmother, not because she was nice to him and he has nowhere else to go. Or whatever.

I do this for each “issue” that the first draft had, for every scene. Sometimes a chapter might require only one or two changes, sometimes it will be more than a dozen (and may need to be entirely rewritten).

4. Reviewing Plot Structure and Rearranging Scenes

Often, the massive changes required of a second draft mean that scenes will be deleted or added or moved around. This is the number one reason I like Scrivener—it makes it really easy to re-order chapters, no cutting & pasting required.

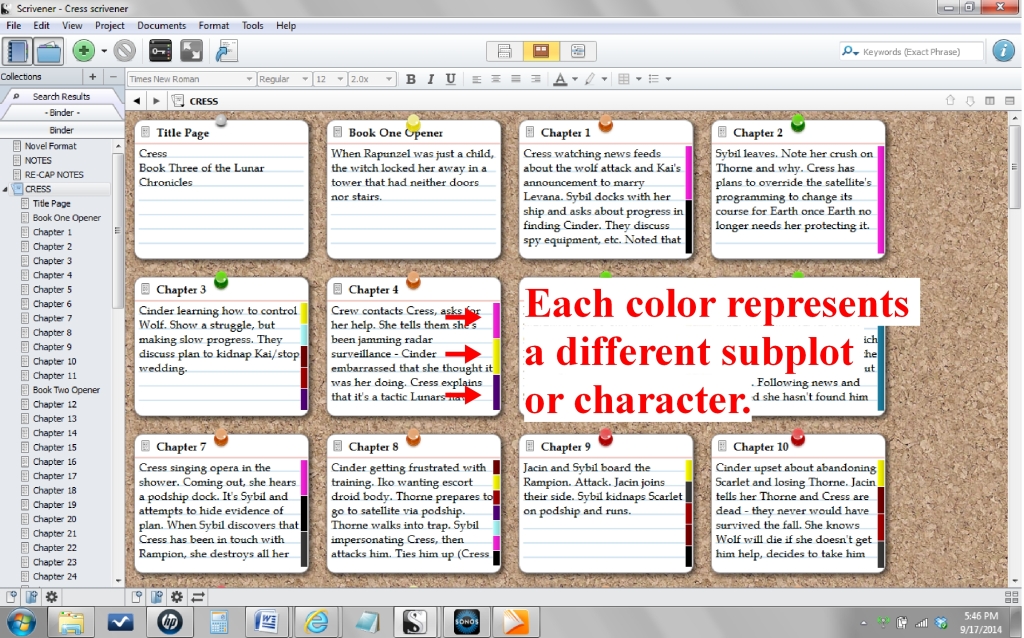

As I rework different elements of the plot, I’ll often use the “corkboard” function in Scrivener to see if the order of chapters are still making sense and rearrange as necessary. I’ll update the synopses of chapters as they evolve so I can always see, at a glance, how the story is progressing from scene to scene to scene.

I’ll once again think about plot structure. Is my “inciting incident” accounted for, and can it be more intense? Is the suspense building consistently and leading to a satisfactory climax, or do I need to up the stakes somewhere?

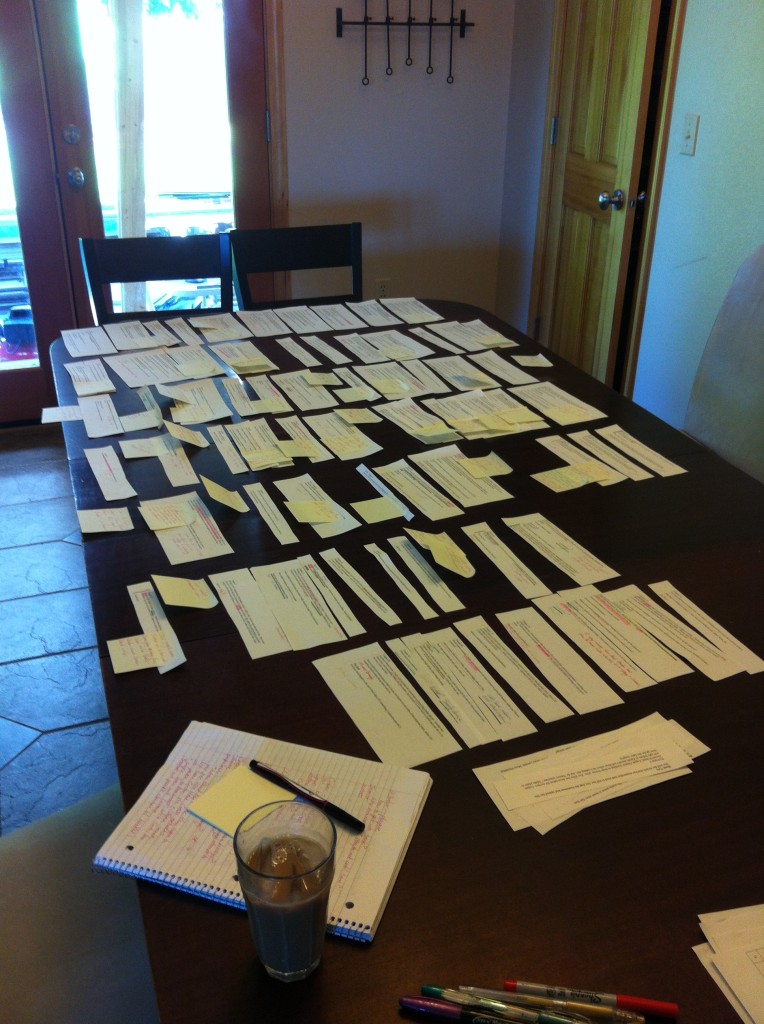

Not using Scrivener? A technique I used before (and still sometimes use when a plot is extra complicated and I need more flexibility than Scrivener gives me), is that I print out my scene list (see #2, above), cut each chapter into its own strip of paper, and spread those out on a large table. Then I can rearrange them in the same fashion, once again able to see the “big picture” all at once. Be sure to leave space in each scene to add notes as you brainstorm.

(Re-arranging the plot without Scrivener.)

5. Developing Subplots

During the outlining and first draft stages, I’ll no doubt uncover some subplots and they’ll no doubt factor into the major arcs of the story, but they don’t usually get fleshed out until the second draft because I was focused on the major plot before.

Now it’s time to start exploring those subplots in more depth, expanding them, and connecting them to the main plot in a way that feels natural.

In the first drafts of both Scarlet and Cress I was almost entirely focused on the major plots of the title characters—Scarlet and Wolf seeking out Scarlet’s grandmother; Cress and Thorne trying to survive the desert and get back to the ship. Meanwhile, I had a chapter here and there of the secondary plot (Cinder trying to learn more about her past; Cinder trying to stop Levana), but it was relatively sparse until the point where the subplots merged.

It wasn’t until the second draft of each book that I really focused on these and other subplots, i.e., pretty much any Kai or Levana scene!

When I’m planning out my second draft, I take stock of the subplots—what’s going on with the minor characters? Does the villain have their own arc? Are there things happening in the story world that need more development (such as a war or the ongoing spread of a plague)?

Once I pinpoint a subplot, I ask myself if it has a beginning, middle, and end, just like with a major plot, and if those points flow together in a natural way.

NOTE: SCARLET SPOILERS AHEAD.

In the first draft of Scarlet, I’d written the chapters in which Cinder and Thorne escape from prison and make it to the Rampion, and I’d written the end where they find Scarlet and Wolf and drag them out up into space. I maybe had a scene or two in between, but otherwise, there wasn’t much happening with those two characters.

So in planning out Draft Two, I had to figure out what they were doing in between these two major points of the story. How and why do they go find Scarlet? How are they spending their time aboard the ship? What is Cinder’s goal in this book and how does she pursue that goal? How can I maintain some romantic tension between Cinder and Kai when they never see each other? And also… Iko!

All these questions lead to ideas for new scenes. After that, it’s a matter of fitting them into the major plot (Scarlet and Wolf) in a way that felt balanced and natural. Easier said than done, ha!

END SCARLET SPOILERS

For more complicated books, like Cress and Winter, I used Scrivener to add keywords denoting subplots in each chapter, so that when I was looking at my corkboard I could see how often and at what intervals each subplot was mentioned. That way, I can see at a glance that, for example, Kai hasn’t been mentioned in the last twenty chapters (nooooo!!), which tells me that I should insert a Kai-centric chapter, or at least remind the reader about him somewhere in those twenty chapters.

Not using Scrivener? I’ve done a similar trick using colored sticky notes or colored game pieces from board games and placing them on my scenes (as described above).

(Denoting subplots using game pieces… just in case you weren’t yet convinced of how neurotic I am about this sort of thing…)

(Denoting subplots using game pieces… just in case you weren’t yet convinced of how neurotic I am about this sort of thing…)

6. Always Make it Worse

And by “worse,” I obviously mean “better.”

I often find that I go way too easy on my characters in the first draft. Characters fall in love and get that first kiss way too early. The villain is too easily vanquished. The protagonist too quickly finds a solution to their problems.

The second draft is where I start making it worse for the characters. How can I challenge them? How can I test them? How can I push them beyond their limits? What cruel, awful things can I do to them now?

Sounds sadistic, I know, but this is where conflict and suspense come from. If you’re going too easy on your character, the reader will get bored.

Always be asking yourself, during every draft: How can I make this worse?

7. Write (Rewrite / Revise) until you have your Second Draft

By the end of all this prep work, I should have a manuscript that’s been rearranged and restructured in a way that will (hopefully) tell the story in the most optimal, suspenseful way possible. In each chapter I’ve listed a series of notes for the things that need to change in that specific chapter. I’ve added placeholders for brand new chapters and summarized what they’re going to be about. I’ve moved any chapters that are no longer applicable into a “deleted scenes” folder (because I’m paranoid about actually deleting anything).

Then… I start rewriting!

Like with the first draft, I give myself goals, such as “revise 2 chapters per day.” I also aim to write lineally, but like with the first draft, if I get stuck or am inspired to work on a chapter later in the book, I’ll do that if that’s what I need to keep up my momentum.

Compared to my fast first drafts, the second draft is sloooooooow. Anywhere from three to nine months slow. (At least, that feels really, really slow to me.) In this draft, I’m not so much trying to get through the story fast, rather I’m trying to savor the story and let my imagination explore the world and the characters and the plot while I’m rewriting it, so that I’m open to fun, new, magical ideas if they come to me. I’m much more focused on making the story click together as a whole and make sense and start to be somewhat readable.

My second drafts change a lot. With Cinder, I’d estimate I only salvaged about 10% of the first draft. Alternatively, with Heartless, I’d say about 50% of the second draft was new material. So the percentage has gotten better with each book, but . . . I’m still rewriting a lot, a lot.

It still won’t be perfect—far from it!—but this is the draft where it starts to feel like a real book.

After I’ve finished, I give it another simmering period before moving on to additional revision drafts, which I’ll get into next week.